About Maus

A serious turn . . .

Things seem very strange in our world today. So it seems like a good time to talk about one of the most brilliantly Misfit books ever created.

I started thinking about Maus after seeing mention of a new documentary film about the life of writer Elie Wiesel—a Holocaust survivor and Nobel Peace Prize winner.

The waning months of 2025 seem like a good time for more people to know about Elie Wiesel’s work. And about Art Spiegelman’s incandescently original graphic memoir.

So here’s a slightly dry summary I wrote in one of my former lives . . .

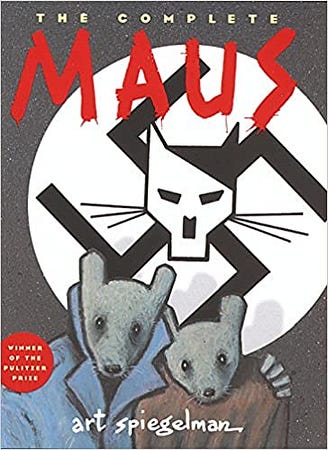

The Complete Maus is a graphic chronicle of artist Art Spiegelman’s attempt to understand his father’s life, his mother’s death, and his own identity. To say it is unique is to say the least.

Spiegelman’s Jewish parents were both Holocaust survivors — or it might be more correct to say that they outlived Hitler. Like many who survived physically, they were haunted by the experience for the rest of their lives.

And like many children of Holocaust survivors, Spiegelman grew up with a sort of shared trauma. Parents often did not want to talk about what had happened to them — but that very silence, set against a family history filled with tragic loss, affected their children deeply.

Some Background

Spiegelman’s parents relocated to Sweden, where he was born in 1948, and then to the United States, where he grew up. In 1968, as a college student, he suffered a brief but severe mental breakdown — and soon after, his mother Anja committed suicide. His father Vladek was a difficult personality, often clashing with his son and his second wife.

During the 1970s and 1980s, Spiegelman achieved success as an artist and publisher in the world of experimental comic books (sometimes referred to as “comix”). But he continued to struggle with unresolved questions about his parents and his family’s past. In 1978 he began recording conversations with his father, and traveled to the infamous Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp, where his parents had been prisoners in 1944.

By the time his father died in 1982, Spiegelman had already produced some of the material that eventually became Maus: A Survivor’s Tale. The first volume, subtitled My Father Bleeds History, was published in 1986.

The Art

Maus is as much a work of visual art as a work of literature and history. Like conventional comic books, it is composed in panels, with bubbles for the text — but the richly detailed drawings and the skillful writing work together to create a literary effect that is very different from ordinary comics.

There was already a growing body of graphic literature in the 1980s, but Maus was the first such work to reach a wide audience. Spiegelman’s creative and surprising treatment of Holocaust subject matter attracted a great deal of attention — especially due to his use of anthropomorphic forms. The book’s Jewish characters have the heads of mice (“maus” is the German word for “mouse”), while German characters have the heads of cats.

Other nationalities are also shown as animal species, adding a layer of visual interpretation that is both shocking and thought-provoking. Although this approach initially aroused controversy, it has come to be seen as one of the work’s most powerful qualities.

The Narrative

Volume 1 of Maus tells the story of a dashing young Vladek, his courtship of Anja, and his conscription into the Polish army. After a failed escape attempt, the Spiegelmans are deported to Auschwitz — and the book ends as Anja, Vladek and their first son Richieu are separated at the gates of that notorious concentration camp.

The account of Vladek’s pre-Auschwitz experiences is framed in the book by flash-forward views of his troubled later life. Spiegelman, who appears as himself, reveals the strained relationship between father and son, depicting the slow, often difficult process of their interviews.

In the second volume, subtitled And Here My Troubles Began, both stories continue. Vladek’s Auschwitz ordeal is recounted in grim detail, along with his stubborn and resourceful campaign to survive. He is finally reunited with Anja, but their son Richieu is never found.

Spiegelman’s own character struggles with guilt over the commercial success of Maus I, and spends time with a psychiatrist who is himself a Holocaust survivor. The final panel of Volume 2 is a simple drawing of Vladek and Anja’s headstone, with Spiegelman’s signature beneath.

Afterward

Following publication of the second volume in 1991, Spiegelman received a special Pulitzer prize. Both volumes were published together as The Complete Maus in 1997. An extensive body of criticism has developed around the work, which offers a complex, nuanced, and deeply affecting perspective on the Holocaust and its legacy.

In 2011, Spiegelman responded to the book’s continuing popularity with MetaMaus: A Look Inside a Modern Classic, Maus. It includes interviews, photographs, and other materials, offering further insight into both his creative process and his family history.

For most writers, being a Misfit is awkward and/or unprofitable at worst. But for some, the challenge runs further and deeper—so I find it good to know that we can go very, very far out on a creative limb, and find that it still supports our weight.

I’ll be back on Friday with some lighter fare. C